Aerospace backpack gives patients with ataxia greater stability

A backpack featuring aerospace technology can help people with the movement disorder ataxia to stand and walk more steadily. In the long term, the backpack could be a useful balancing aid for people with ataxia, reducing their dependence on a walking frame. This is according to research conducted by Erasmus MC, Radboudumc and TU Delft.

Ataxia is a neurological disorder in which the cerebellum does not function properly. This leads to problems with coordination and balance, among other things, putting people with ataxia at greater risk of falling. Rehabilitation physician and principal investigator Jorik Nonnekes of Radboudumc: ‘Some people with ataxia, often young people, are dependent on a rollator. These are heavy and can be awkward to use. Moreover, people with ataxia often experience the rollator as stigmatising.’

Technology from space

The backpack, called the gyropack, contains technology used in space travel to stabilise large satellites or space stations. The gyropack has been in development for more than ten years by the group led by engineer Heike Vallery at TU Delft and Erasmus MC. “When I heard about it, I thought: I can use this to help people with ataxia,” says Nonnekes.

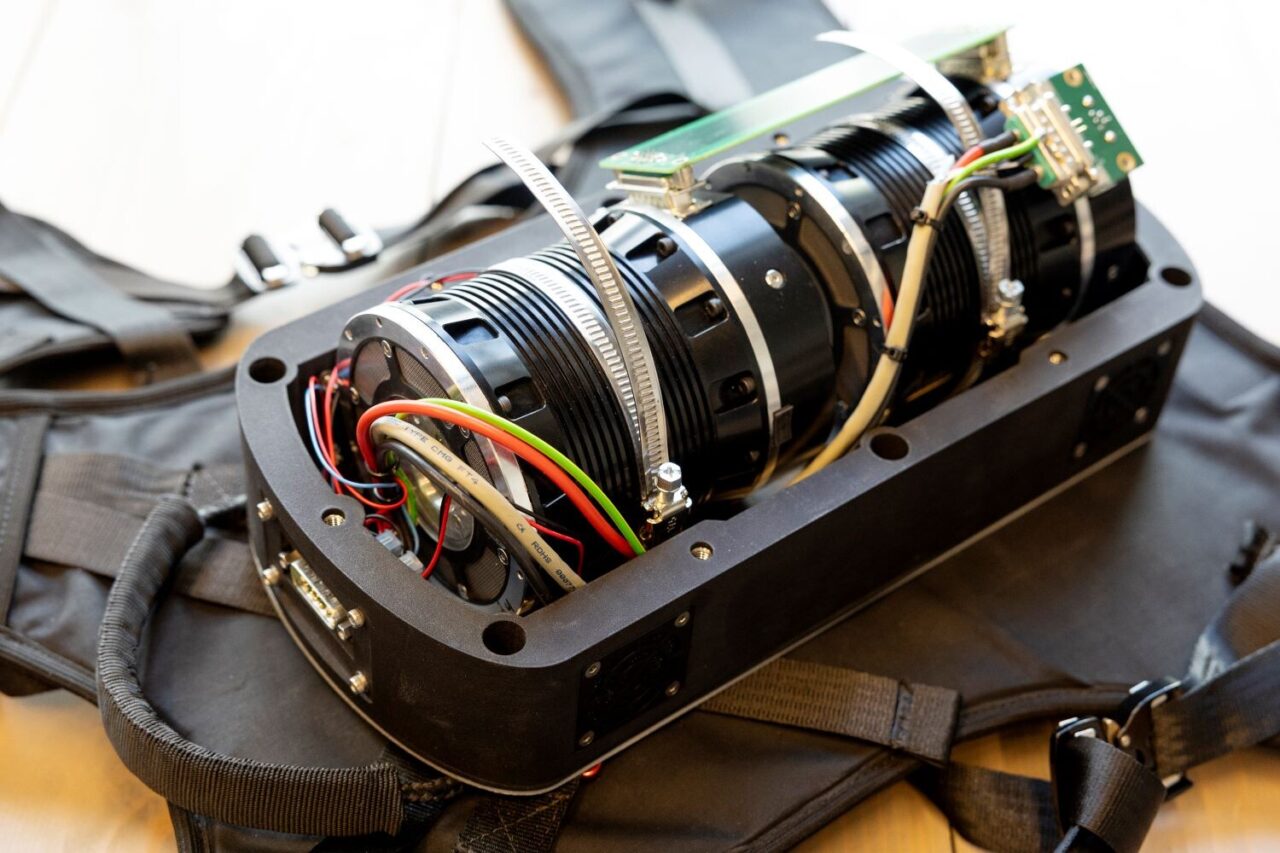

The backpack contains spinning wheels and a complex control system. ‘Inside the backpack, you will find two cylinders, or soup cans, as we call them,’ explains engineer Bram Sterke of Erasmus MC. He developed the backpack together with Vallery. ‘The cylinders contain a flywheel that spins rapidly. Just like a spinning top, the flywheel tends not to change its orientation. The cylinders also contain a motor that manipulates the flywheel.’

Vallery explains that this creates resistance to the twisting motion of the torso, which is a bit like moving in water. This causes the person wearing the rucksack to move their torso more slowly, making them more stable and giving them more time to adjust their balance themselves.

The researchers tested the backpack on fourteen patients with moderate to advanced ataxia. They performed balance and walking exercises in three situations: without a backpack, with an active backpack, and with an inactive backpack. The latter situation was indistinguishable from the active variant in terms of sound and feel.

The experiments showed that even when inactive, the backpack already offers added value for patients. ‘This is probably because the backpack is quite heavy, weighing around six kilograms. That in itself helps to keep the upper body stable. However, the greatest improvement in balance was seen with the active backpack. Patients were visibly more stable and were able to walk in a straight line more easily, for example,’ explains Nonnekes.

Future prospects

The researchers now want to further develop the backpack, with user-friendliness being the top priority. ‘At the moment, it feels like you’re walking around with a vacuum cleaner on your back when you wear the backpack,’ says Sterke. ‘So, in the short term, patients won’t be wearing it to the supermarket; we first need to make the backpack lighter and, above all, quieter.’

Nonnekes hopes that in the future, the backpack will make everyday life easier for people with ataxia: ‘So that they can go to a party without a walker, for example, which some people find cumbersome and awkward. That gives them much more freedom of movement and hopefully improves their quality of life.’